What Is a Stablecoin? (But Actually)

What are stablecoins? What do they do in DeFi? Why do people mint stablecoins? Where are stablecoins right now?

Thanks to ChainlinkGod, Luca Prosperi, Zubin Pratap, and Gerrit Hall for their help on this article.

For those looking for some code, we have a stablecoins folder in the defi-minimal project.

When you look up “what is a stablecoin” you get a lot of *pushes glasses up* wrong or misleading information.

The wrong and misleading information is:

- All stablecoins are pegged/anchored to that of another asset/currency

- All stablecoins fall into the categories of fiat-collateralized, crypto-collateralized, and algorithmic

And I’m here to straighten the record and tell you EVERYTHING you need to know to really understand stablecoins. What are stablecoins, what they do in DeFi, why they are so important, and where they are right now.

And additionally, probably the most important and interesting part of the picture, how stablecoins are created and the economics behind them. This isn’t your average stablecoin article, but your end-to-end mega stablecoin article.

Buckle up, because we are in for a volatile ride about stability.

Table of Contents

- What is a stablecoin?

- Why do we care?

- Categories and anatomy

- A look at various modern coins

- Who pays for stablecoins?

- What’s the deal with curve wars?

- Final thoughts

What Is a Stablecoin?

A stablecoin is a non-volatile crypto asset.

That’s it.

If you take away anything from this article, please, have it be this:

A stablecoin is any crypto asset whose buying power fluctuates very little relative to the rest of the market.

“Non-volatile” means that a crypto asset’s buying power will stay similar for a long duration of time. “Similar” and “long” are subjective terms, so we’ve already learned that a stablecoin is subjective from person to person! Stable to you might not be so stable to someone else.

“Buying Power” is how much a currency can buy. If one dollar can buy you a box of apples today and in ten years, we would say the buying power of that currency stayed stable over 10 years. If after ten years one dollar could only buy half a box of apples, we’d say the buying power of the dollar was cut in half. We give more buying examples later in this blog.

An asset whose price jumps up and down would not be considered a stablecoin. Most crypto assets are volatile in nature or have the capacity to be volatile.

The second most important takeaway is this:

Almost every question you have about the purpose of stablecoins can be answered by swapping out the word “stablecoin” for “dollar” in your question, and asking “well, how does a dollar, Euro, or Yen handle that?”

For example:

Question: Why are stablecoins important?

Has nearly the same answer as:

Question: Why are dollars important?

Why Do We Care?

In our daily lives, a low-volatility currency is very important for three reasons:

- Storage of Value: So that we can build wealth or bartering power. Having your dollars in a bank account is using them as a store of value.

- Unit of Account: A way to measure how valuable things are. Like when you go to the store and see goods listed in terms of dollars. Dollars are acting like a unit of account.

- Medium of Exchange: An agreed-upon method to transact between each other. When you use a currency to purchase items, you’re using it as a medium of exchange.

In order for our everyday lives to be efficient, it’s good to have a currency or coin that accomplishes these three goals. Most crypto assets like Ether or Bitcoin don’t accomplish all three goals very well. Now some would argue they are good at all three, but I’m quite certain that they do a terrible job of at least unit of account.

If I were to go to the Crypto Amazon online store and we had Ethereum or Bitcoin as the unit of account, based on the day of the week the prices could be twice what they were the week before. This high volatility makes for a poor unit of account.

Now, an average stablecoin article would stop there, or go deep into the history of money, but we have bigger plans… Let’s look at what a stablecoin looks like, then we will jump down to the top stablecoins.

If this next section is a little confusing, feel free to skip down to the top stablecoins section.

Categories and Anatomy

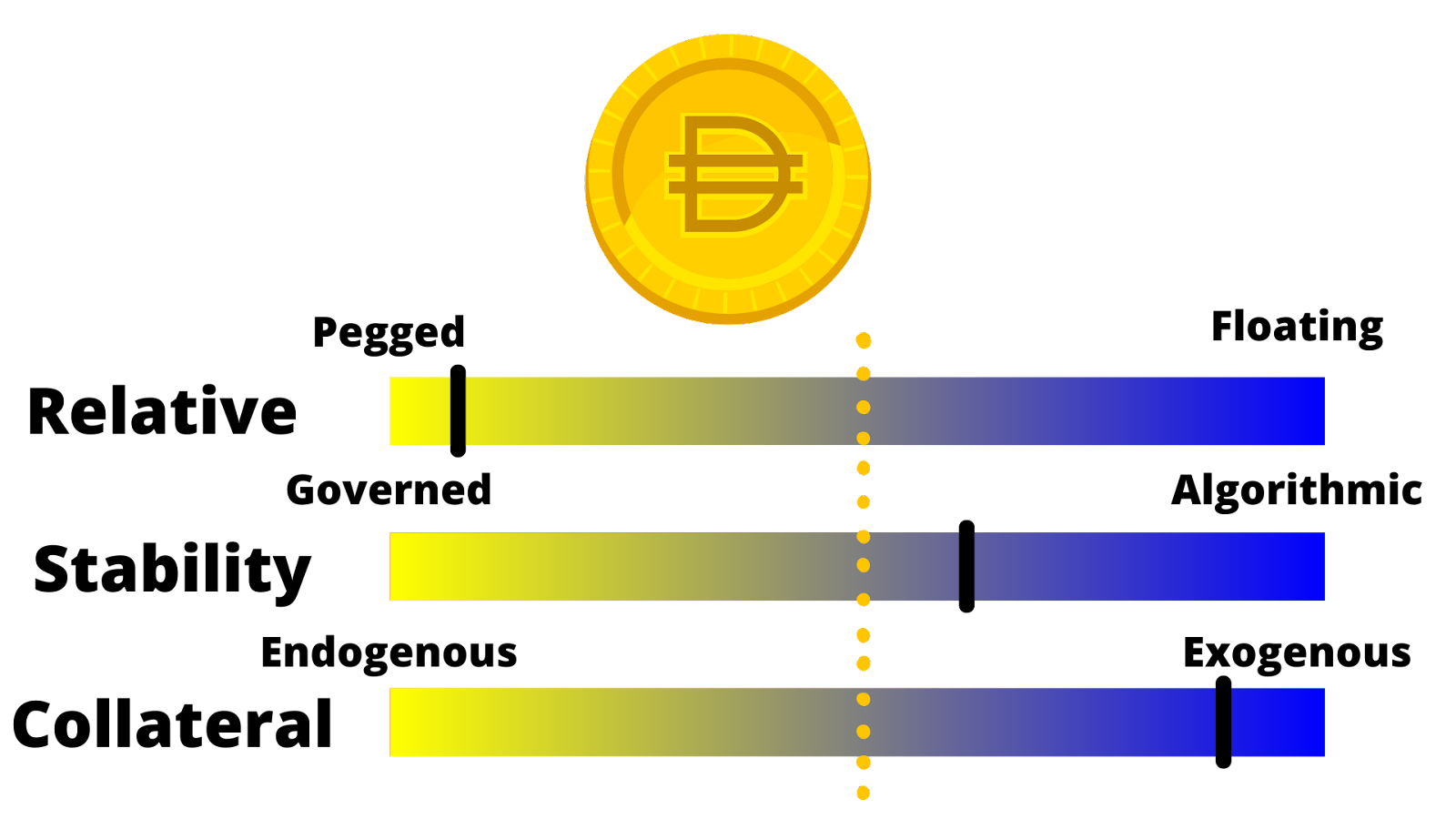

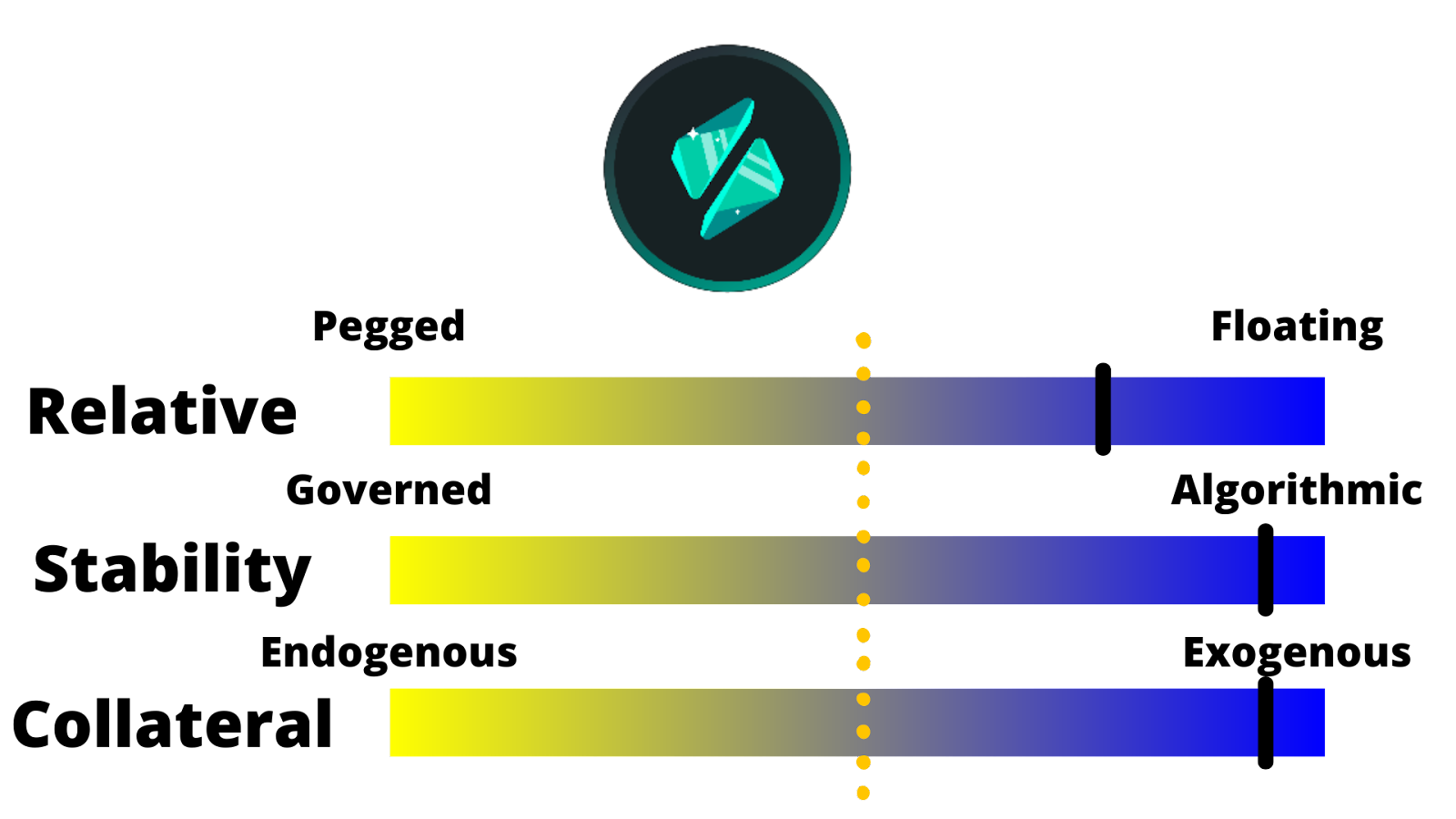

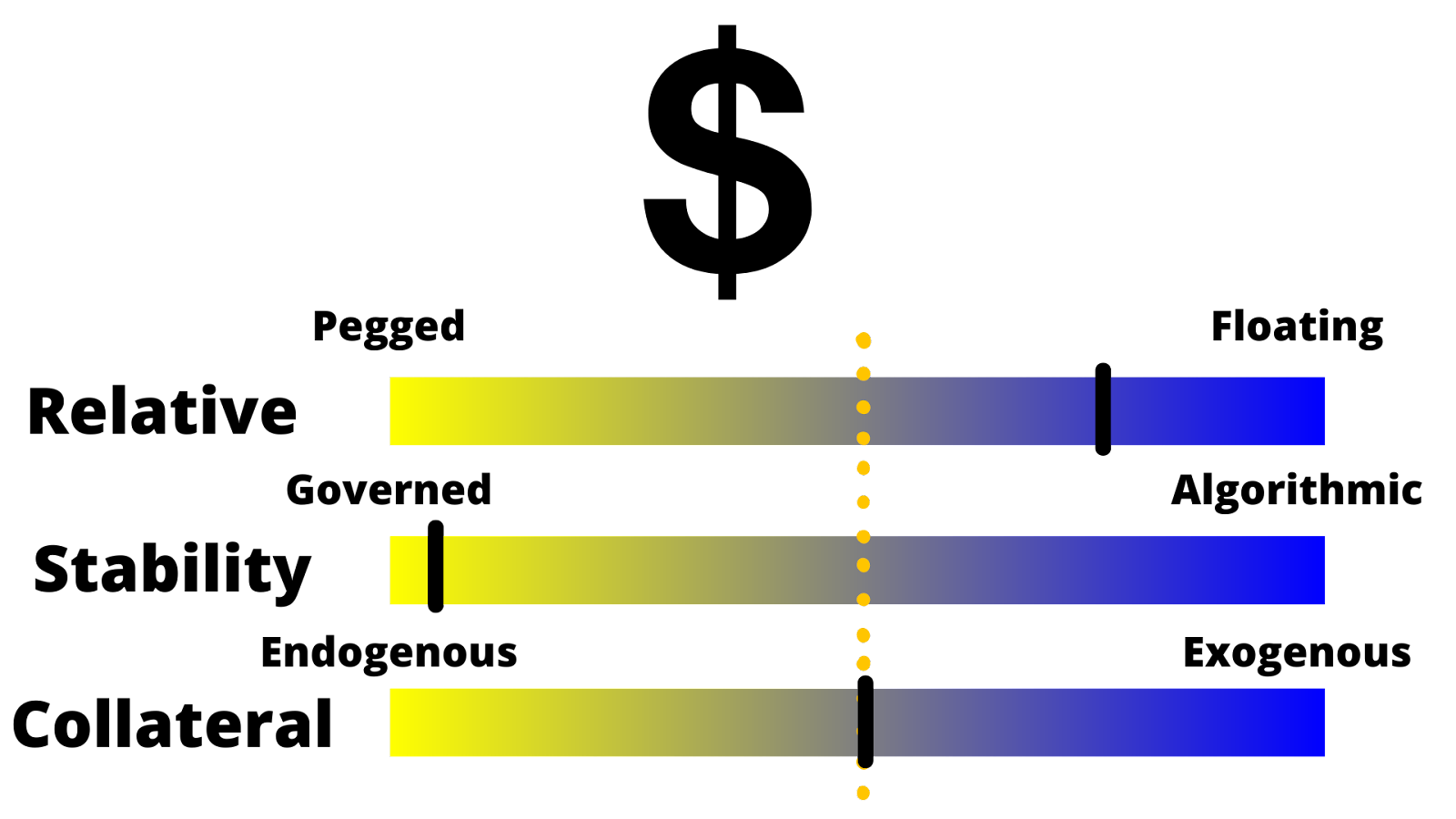

Now in order to make or use a stablecoin, you have to understand the 3 main categories of a stablecoin.

- Relative Stability. Pegged/anchored or floating.

- Stability Method. Governed or algorithmic.

- Collateral Type. Endogenous or exogenous.

These categories are each spectrums, meaning a coin can be more algorithmic or more governed by its stability method. It can be more exogenous or more endogenous for its collateral type. And more pegged or more floating depending on its implementation.

Let’s understand each of these categories and the tokens that fall into them.

Relative Stability

As mentioned above, a stablecoin is only stable as a relative term, so we need to know what we are comparing our stablecoin to that makes them stable.

Pegging/Anchoring

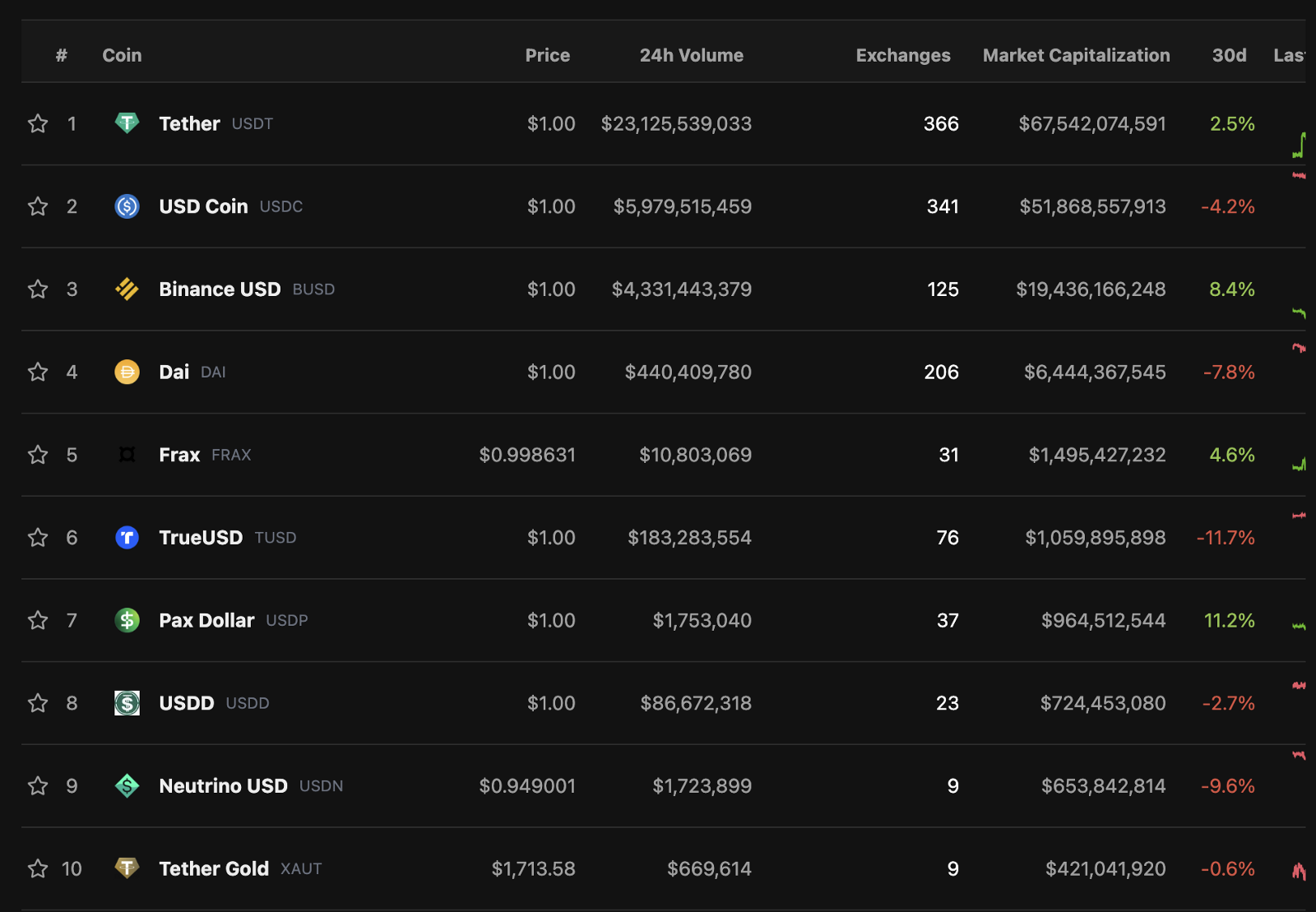

One of the easiest ways to make a stablecoin would be to back it by or peg it to another asset that most people consider “non-volatile.” So yes, some stablecoins are pegged to another asset, but not all (more on that later). The most popular asset most people choose is the US dollar. Many stablecoins like USDT, DAI, and USDC follow this strategy.

A stablecoin that is “pegged” or “anchored” to another asset is a stablecoin that follows the buying power of another asset that people consider to be stable, like the Dollar, Euro, or Yen.

They then follow the narrative of:

One Dollar-Pegged Coin (USDT, DAI, or USDC) = $1

Which is easy for people to understand. The way pegged stablecoins work is they have a smart contract or service which says at any time (usually any time) you can swap your coin for its underlying collateral. With our dollar-pegged stablecoins, you can swap your DAI, USDC, or USDT for the dollar equivalent.

For example, with DAI, the protocol enables you to trade your DAI in for your ETH collateral at any time, at an exchange rate of exactly \$1 of collateral per 1 DAI. So if you have 100 DAI, and you had ETH down as collateral, you can trade your DAI in for \$100 in ETH via a smart contract. Boom! Now that we have a (roughly) permanent exchange for the currency where the price of one DAI is always $1.

Pegged Asset Examples: DAI, USDC, USDT, FRAX, UST

Floating

A token can go the “non-volatile” route and follow a “pseudo-index” like route and create a stablecoin whose buying power stays relatively the same over time — without it being pegged to another asset. Relatively speaking, the coin would still be stable by very slowly following current market conditions, but is resistant to the quick spikes and dumps of the market. You could think of a floating stablecoin as an oobleck-like substance, but in the financial market. It’s firm when markets are volatile, but liquid when change comes slowly.

Another analogy is a board “pegged” to a dock vs. a buoy “floating” by a dock compared to the water. The “pegged” board might seem more stable at first, but when the tide is in, the pegged board is underwater and the buoy is still floating in the same position.

Coins like RAI follow this principle. They “float” around a price that very slowly follows the market, trying to keep the buying power of the coin the same at all times.

A non-pegged token might be difficult to wrap your mind around but just remember, in order to be a stablecoin its buying power just has to be relatively stable. So a coin that fluctuates around $2.10 always, could be considered a stablecoin even though it is worth a weird amount of dollars.

You could even have a floating stablecoin be more stable than a dollar-pegged coin, for example:

If 1 Cheesecake in 2018 is worth \$45 and 1 cheesecake is worth \$55 in 2022, one could say the buying power of the dollar went down by ~20% in those four years. Inflation (CPI) is usually a good measurement of the instability of the dollar. If we had a coin (let’s say “Cheesecake Coin”) that could buy 1 cheesecake for 1 Cheesecake Coin in 2018 and 2022, the buying power of that coin stayed the same across the four years, making it a relatively more stable stablecoin than a dollar-pegged one.

Anyways…

I won’t get into the mechanics of a coin like RAI here, as it’s pretty difficult to explain how they work without getting into the other properties of the coin. We will explain RAI more later on.

And will we be talking more about those in this article? You bet we will.

Floating Asset Examples: RAI

An Example

To further clarify the difference, let’s take a buoy and an anchor as examples.

If you asked “is the anchor or the buoy more stable” how would you answer? Well, it depends on what you need it stable for.

If you’re looking for stable in relation to the ocean floor, the anchor is more stable. But if you’re looking for stable related to sea level, the buoy is more stable.

This a solid pegged vs. floating analogy. One may go further with the analogy and ask “what happens when a temporary storm comes, wouldn’t the buoy start rocking all over the place and going up and down, making it not stable?” To that I’d say, yes. This is why a lot of protocols like RAI account for that with built-in mechanisms to slow down rapid temporary changes. Imagine a buoy that stays at sea level, unless there is a storm. A “magic buoy” in a weird sense

You might even ask “well, isn’t the buoy sort of anchored then, since it needs to be tied down somewhere to stay in the same place?” To that I’d also say yes. A stablecoin that keeps its buying power can be thought of almost as an asset that tracks a sort of consumer index, or the long-term market movements of its underlying collateral. But we might be going a little too far down the analogy rabbit hole.

Stability Method

The stability method is the way the coin stays stable. It is on a spectrum of algorithmic to governed, where either it’s 100% automated by an algorithm, or it has some form of human intervention.

Algorithmic

An algorithmic stablecoin is any coin that uses an automated algorithm that, usually, mints or burns tokens in a specific way to keep stability.

The stability method could also be called the “supply mechanism” or “mint and burn” mechanism since they are so closely tied. These algorithms can also vary a LOT in how they are implemented. Rebasing, supply and demand games, and other oracle-based ventures are all different algorithms that many stablecoins use today.

Algorithmic Examples: DAI, FRAX, RAI, UST

Governed

A governed stablecoin is one where a central issuer chooses when to mint and burn tokens. Now, this could be put to the extreme, where one person is doing the minting and burning, but it could be more algorithmic if there is perhaps a DAO voting on when to mint and burn. The Maker protocol is a fantastic example of how an algorithmic stablecoin can have a lot of governed properties—since the DAO controls so much of how the protocol operates.

A lot of times, centralized stablecoins are easily in the governed category, since a single off-chain entity controls their minting and burning.

Governed Examples: USDC, USDT, TUSD

Summary

A token can have both algorithmic and governed mechanisms, and be on the spectrum of being more decentralized and algorithmic to more centralized and governed. With this definition, the DAI token would fall into the algorithmic category. USDC would fall into the governed category, being a deeply centralized stablecoin. Traditionally-thought algorithmic coins like the original LUNA/UST would also be considered algorithmic.

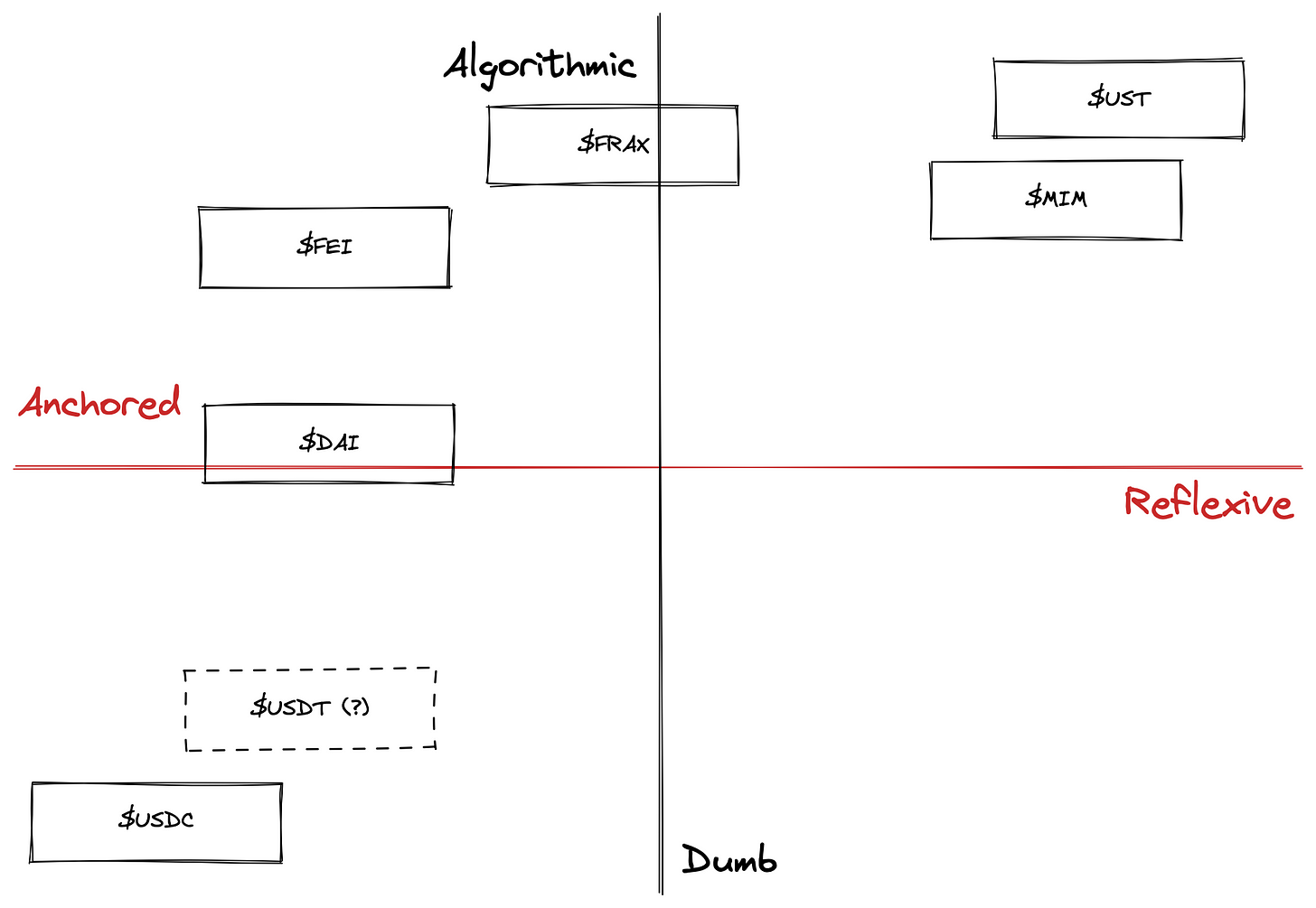

The Dirt Roads article gives a great visualization of popular stablecoins and where they are on this spectrum. He uses “dumb” as the opposite of Algorithmic, which I don’t think is a bad replacement for governed.

The part we haven’t discussed is his anchored vs. reflexive spectrum. However, that comes next in the collateral section.

If we look at classically categorized “fiat-collateralized” stablecoins, they almost all fall into the “governed” side of minting mechanisms, since some single entity is doing the minting. Crypto-collateralized tokens like DAI have a governance process but are more algorithmic in the algorithmic-governed spectrum.

Collateral Type

The final and most important categorization of stablecoins is their collateral type. There are two types of collateral that protocols use, ranging on a spectrum once again, endogenous and exogenous.

Now, these two collateral types can be a little tricky to define, but as a test, you can ask:

If the stablecoin fails, does the underlying collateral also fail?

If yes, it’s endogenous; if no, it’s exogenous. Endogenous roughly means the collateral is embedded within the protocol, and exogenous means the collateral is completely different from the protocol. Some other good tests that people use are:

- If the collateral was created for the sole purpose of being collateral

- If the protocol owns the issuance of the underlying collateral

Exogenous Example: ETH is collateral for the DAI token. If DAI fails, does ETH fail? No, ETH still has smart contract uses outside of DAI and will continue to thrive. Therefore, the ETH collateral is exogenous.

Endogenous Example: Very roughly, the underlying collateral of UST was LUNA. In order to mint UST, you needed to burn LUNA, and vice versa. They were designed together at the protocol level, so very “in-bed” together. If UST failed does LUNA fail? Well, this was already proven to be true, so UST had endogenous collateral of LUNA.

It’s this endogenous scheme that most people are afraid of when they traditionally refer to algorithmic stablecoins.

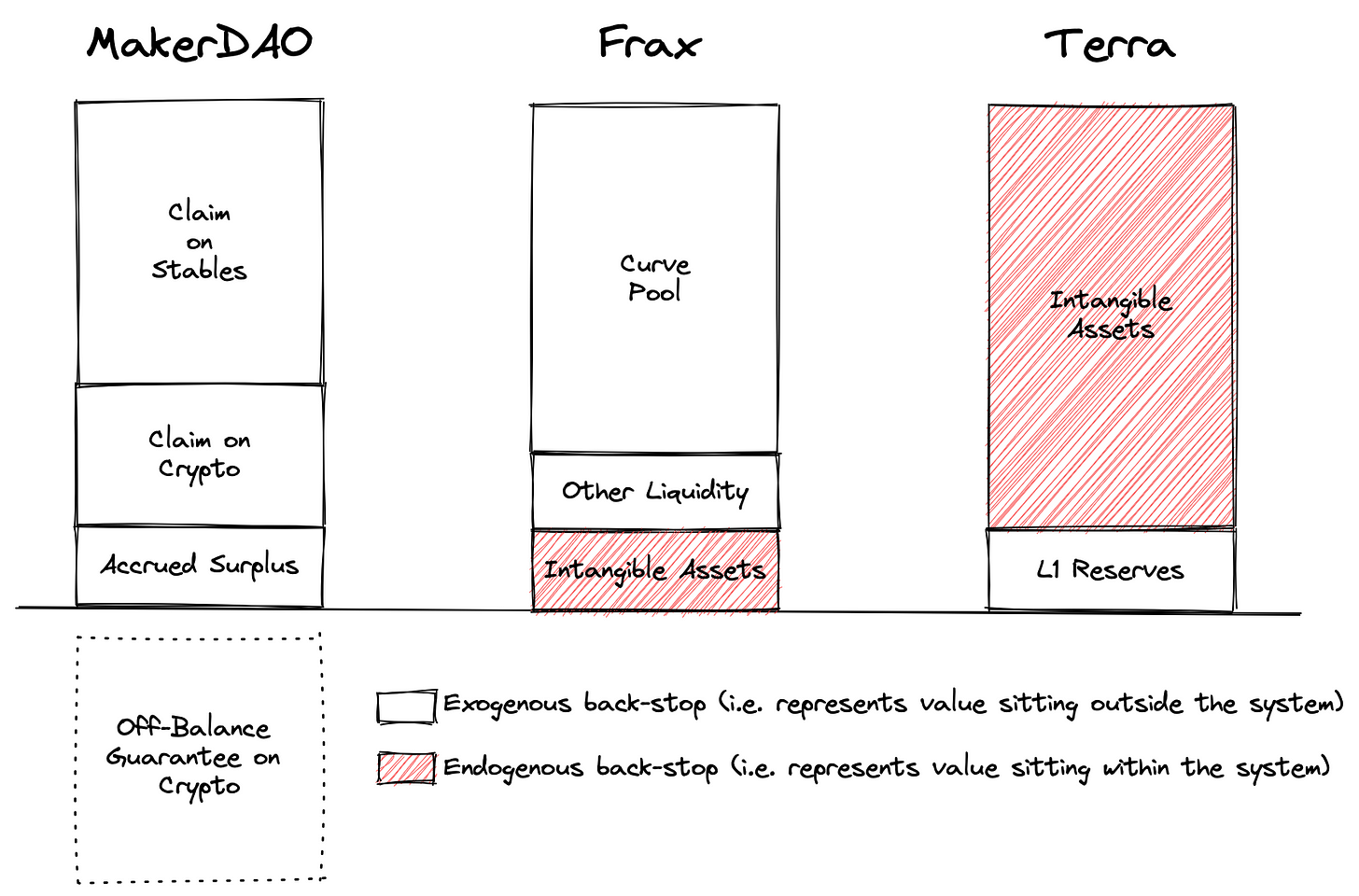

Most stablecoin protocols are 1:1 or overcollateralized, meaning they have more underlying value backing the stablecoin than the total sum of the assets minted, whereas endogenous collateralized protocols can often be undercollateralized. FRAX is interesting in that it has a sliding scale of collateral, and is partially undercollateralized. It can become more exogenous or endogenous depending on current market conditions. The image below illustrates FRAX, DAI (MakerDAO), and UST (Terra).

Endogenous Examples: FRAX (sort of), UST

Exogenous Examples: DAI, USDC, RAI

Now before we put all these mechanisms together by looking at some of the top stablecoins — let’s take a quick pit stop to talk about seigniorage shares. If this section confuses you a little, feel free to skip over it.

When you use endogenous collateral, you can use a stablecoin architecture known as seigniorage shares. The linked paper by Robert Sams is one of the most influential papers fueling the creation of many stablecoins today.

Seigniorage Shares

Seigniorage refers to the difference in cost to create money vs. its value. With stablecoins, protocols often look to create a coin that costs less to create than the value of the coin and is a central idea behind seigniorage shares.

The idea behind seigniorage shares is that you typically have two tokens, 1 token that is stable, and 1 token that “absorbs” volatility. It stems from the idea that tokens are wanted for either:

- Transactional Value (Medium of Exchange)

- Speculation of Growth (Store of Value)

No demand for a coin is generated for its Unit of Account utility — as you just need the coin as a benchmark without actually holding the token.

These two rationales for coin demand are conflicting since with rationale 1: you want your coin’s buying power to stay the same, but with rationale 2, you want your coin’s buying power to be a little risky and hopefully increase. It’s hard to create a token without having both of these factors taken into account.

The idea behind seigniorage shares is to fracture a coin system into two, one that stays stable and captures the transactional value demand, and one that is volatile in nature and captures the speculation of growth. We’ve seen protocols like UST/LUNA and FRAX/FLX approach this, and will probably see more. A lot of these protocols go with the endogenous collateral route as well.

What’s Up with Endogenous Collateral?

A lot of people may be thinking:

So if you use endogenous collateral, you’re basically making value out of thin air. Why would that work, and why would you want to do that?

- Something has value so long as they think someone else thinks it has value

- Endogenous systems hypothetically can scale much quicker

Let’s explore a scenario for point 1.

Schelling Coin Logic

Imagine you have a currency and it’s collateralized 100% by gold. In fact, you run a bank and are open 24/7 to allow people to exchange your bank notes for gold in your vaults. People love the convenience of using your banknotes instead of lugging around their gold, so they treat your currency as if it is equivalent to gold.

Now let’s say the bank is now only open 5 days a week: you need to take breaks anyways! Do your bank notes lose their value now that they can be exchanged for less gold? Probably not — the market probably won’t even care.

Now let’s say you need to close your bank for a week for renovations. Do the bank notes lose their value? Now let’s say you close for a month. A year. A decade. Forever?

If you get past the point where you are closed and will never exchange your bank notes for gold ever again, your banknotes have become the currency, the store of value, the medium of exchange, and the unit of account, without having to be backed by anything.

This scenario is to illustrate that you can have a currency that works without being “backed” by anything (as long as everyone agrees it has value). Most currencies like the US dollar, for example, are no longer backed by another asset. However, one could argue the dollar is backed by the U.S. government’s commitment to its citizens as a kind of institutionally-based agreement.

Scaling Faster

For point two of “Endogenous systems hypothetically can scale a lot quicker,” an endogenous system can skip the step of onboarding collateral. The maximum size of a stablecoin system that depends on collateral depends exclusively on the amount of exogenous collateral all users combined have put into the system. So if the incentive for someone to mint your stablecoin is low, the overall growth of your system will be slower than that of an endogenous system.

Another way to put it is that the supply of the stablecoin is limited by the amount of demand for leverage against the collateral—since people will need to want to mint these stablecoins in order to onboard collateral.

So, a lot of people love this idea and try to make an endogenous stablecoin because of it.

But again, we can see that these coins (Vitalik referred to them as automated stablecoins) can have issues winding down, and when being evaluated, we should keep in mind if they are able to wind down efficiently.

Some Top Stablecoins

DAI

The DAI token is one of the most influential tokens in crypto and is often cited for being the protocol that really kicked off the DeFi craze. DAI was revolutionary as it allowed more sophisticated financial products to emerge on the DeFi scene.

The DAI stablecoin is a pegged, algorithmic, exogenous collateral stablecoin. Now remember, it’s technically algorithmic, but it does have a governance process based on the MKR token and the interest rates of minting DAI, so it’s on a scale of algorithmic to governed. It’s actually a lot closer than you’d think. And now that voting proposals have passed to even allow off-chain collateral into the system, the system has moved farther from the algorithmic mark.

Normally, the way DAI is created is that a user deposits some collateral, like ETH, into a smart contract. Then using an oracle, you are given DAI that in total is less than the amount of ETH you put up as collateral.

For example, I put down 1 ETH, and at the time, 1 ETH is $1,000. I can then mint 500 DAI. I always have to mint less DAI than I have collateral down, hence DAI being an over-collateralized system. The collateral of DAI is exogenous because it’s things like ETH and other cryptos that don’t need DAI to exist. One could argue though, that if DAI goes down, the value of ETH would go down too, so on a sliding scale, they are at least a tiny bit endogenous.

When I mint my DAI, I get charged a continuous stability fee to do so — usually around 2% a year. With this in mind, anyone who holds DAI is really holding someone else’s debt. Every year whoever minted the DAI is charged 2% for you to hold the DAI you have. This is why a lot of people talk about DAI as “debt” or “a loan.”

Now if your collateral falls below a certain threshold (usually, something around 200% of the value of DAI you minted) you can get what’s called liquidated. This is DAI’s solvency policy, to make sure it never has less money as collateral than DAI in the world. Essentially, if your balance of collateral falls too low, someone else can pay back the DAI you minted and get some of your collateral at a discount. So others are heavily incentivized to pay back your DAI loan if you default!

Keep this in mind as we go through these stablecoins. Most currencies are a form of debt.

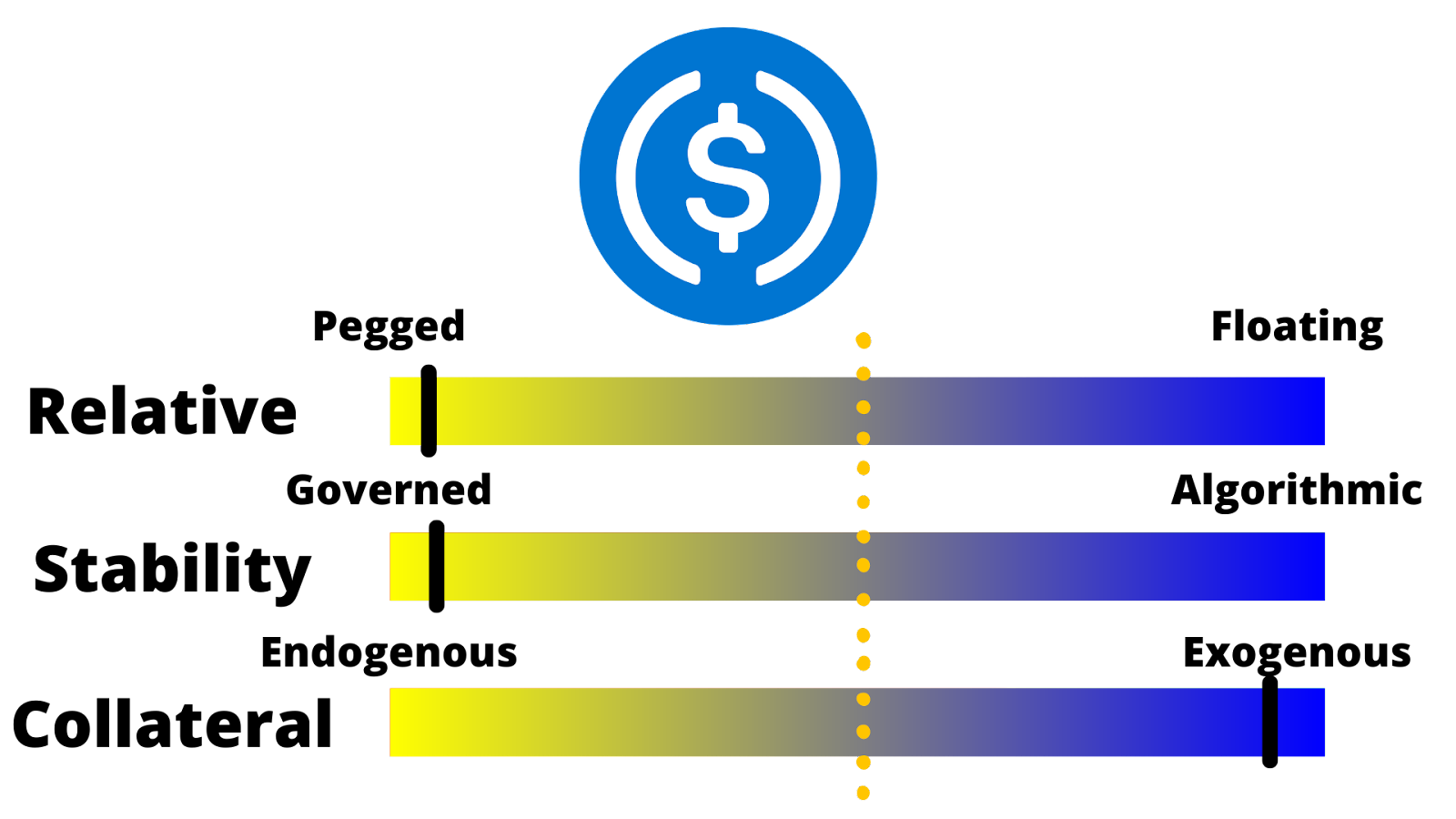

USDC

USDC is the coin behind the joint venture of Circle and Coinbase and is a 100% centralized coin. The team behind the coin can blacklist users and is governed 100% off-chain.

The token is pegged to the dollar and is supposed to be backed 1:1. For every one USDC coin, there is one US dollar in a bank somewhere. Sometimes, they invest these dollars in other assets, so it might not even be backed by dollars but anything, like real estate, stocks, bonds, etc.

There are many tokens that have nearly identical setups to USDC, a centralized entity minting and burning tokens, pegged to the dollar, saying their tokens are backed 1:1 with US dollars. Protocols like USDT, TUSD, and GUSD all follow this blueprint.

FRAX

Now that we know more, we can take a look at more stablecoins and start to understand them more quickly. FRAX uses its FLX governance token as part of its collateral as well as other tokens, and is known for being undercollateralized. This makes the token slightly endogenous since one of the underlying collaterals (FLX) would collapse if the FRAX system collapsed. It’s pegged to the dollar, and is algorithmic in nature, with some governance from the FLX token.

FRAX is our first token on the list to implement a version of the seigniorage shares, but is still collateralized and uses a lot of exogenous collateral as well to prevent what happened with UST. What’s especially interesting about FRAX, is that the amount of exogenous vs endogenous collateral it needs can shift, based on how risky the protocol is at the moment.

UST (With the Original LUNA)

Now we know UST collapsed, but it’s important to reflect on this stablecoin as a cautionary tale of what can happen with algorithmic endogenous coins. UST was a seigniorage shares type coin with LUNA absorbing the volatility so UST could stay stable.

It ended up imploding on itself, as once the UST token lost its peg, more LUNA shares were minted to try to find the peg again when people redeemed their UST for LUNA just as in Robert Sams’ paper. However, as a LUNA holder, you don’t love the idea of more LUNA being minted, since that reduces the price of your LUNA, so if you see the UST peg falling, you start dumping your LUNA. This makes the total collateral of UST fall, meaning the UST loses its peg, meaning more LUNA is minted. More LUNA minted means more LUNA holders panic selling, which means UST losing its peg, which means more LUNA minting, which means more…

Do you see the issue here?

With the circular logic of endogenous tokens, there is a massive risk of these algorithmic systems working correctly. We say that UST/LUNA was reflexive in this sense since the value of the protocol was based on itself.

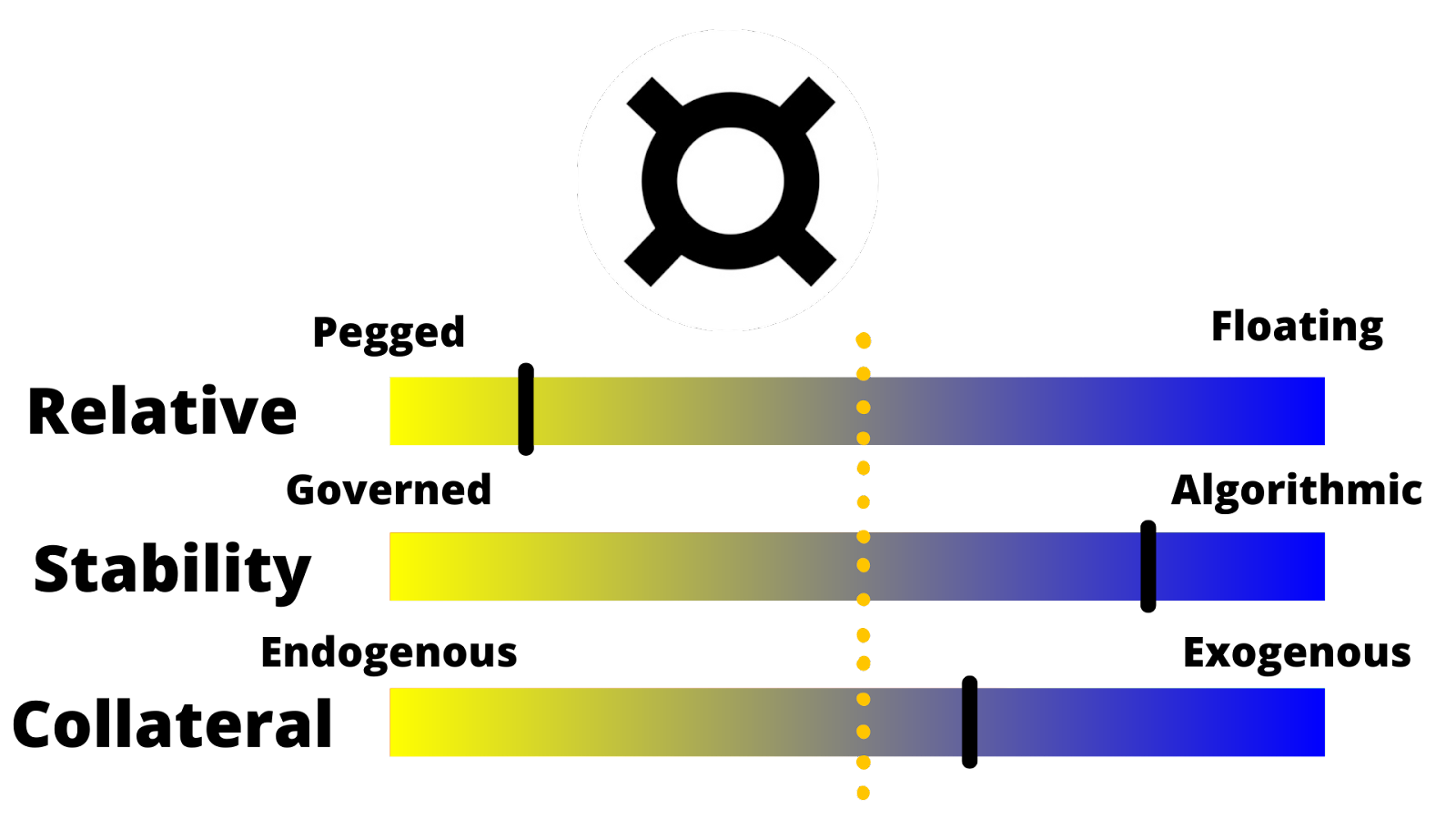

RAI

RAI is one of the few stablecoins that is not pegged to another asset. It was originally up for governance on the DAI project but the Maker group decided to move forward with the protocol as we know it today, so many took off wanting to see improvements like:

- Less governance

- No peg

- More “pure” collateral

If we want DeFi to stand on its own two feet, it would make sense that we wouldn’t peg our currency to the world’s nation-states. Additionally, the more governance in a protocol, the less algorithmic and trust-minimized it is. The purpose of web3 is to make transparent trust-minimized systems, and every piece of governance introduced is another piece that needs to be trusted.

Without going too deep into the mechanics of RAI, RAI is a coin that focuses on two prices, the market price of the coin, and the redemption price. The market price of RAI is the price people are buying and selling the coin at, and the redemption price is how much the protocol will buy your coin for. If the market price of the coin is too high, essentially the redemption price drops, and if the market price is too low, essentially the redemption price rises. This is how the coin is able to keep relatively stable buying power.

You can learn more about it here or, in this video which breaks it down with visuals. Essentially, RAI works similarly to DAI with users depositing ETH to get RAI minted, but the difference is that RAI isn’t pegged to a dollar. It instead uses supply and demand forces (via a sort of interest rate) to create or suppress demand, and has the value of the token very slowly follow where the market goes. This means, your buying power with RAI stays relatively the same over the course of time.

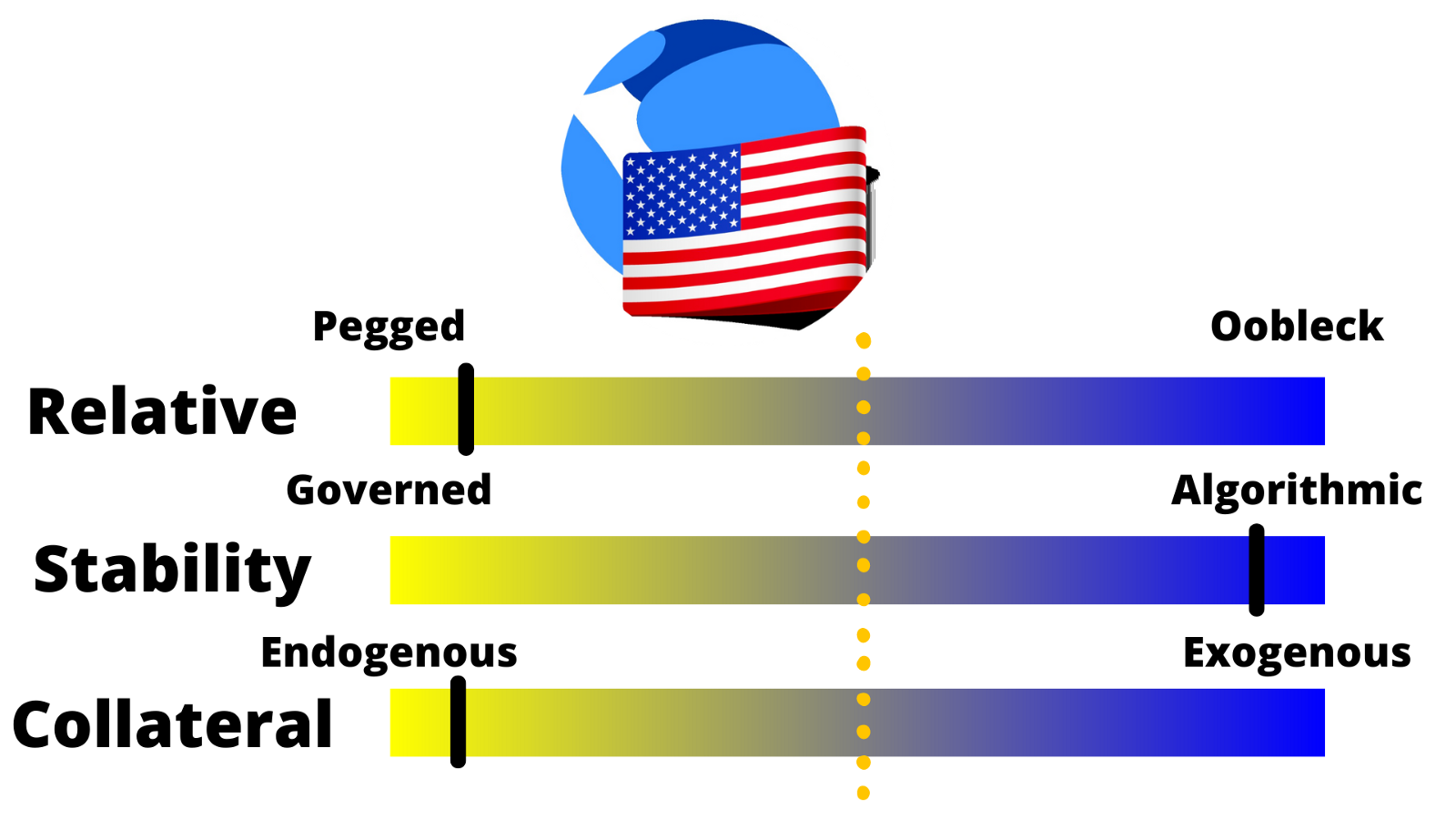

USD (the US Dollar)

“Hold the phone, Patrick. The US Dollar isn’t a stablecoin!”

Yes, you’re right, but using the categorizations we came up with above, they actually apply to all stable-type assets, and the dollar is one of those. And it’s interesting to compare because we want to make a world in Web3 that is better than our current system in Web2.

The easiest category to get correct is its stability — which is 100% governed. Sure they might use some algorithms behind closed doors to decide how much to print, but the monetary policy of the dollar is up to the US government, full stop.

Now collateral is particularly interesting, as the dollar was once backed by gold, but taken off the “gold standard” in the 1970s. Now, one US dollar is worth… one US dollar, which means the dollar is reflexive, and arguably, endogenous in nature.

However, you could argue the answer is no, and that the US dollar is backed by other national assets (political, military, technological, and geographic resources), which would make it exogenous.

So sometimes, it can be hard to tell what an asset is backed by.

Which Stablecoin Is Best?

There isn’t one: each has its tradeoffs.

Each stablecoin makes design choices that make them widely different from each other but accomplish similar things. There isn’t a “best” system, and we are seeing the industry constantly change.

Who Is Paying for Stablecoins?

Now that we have all this background information, we can get to the good stuff.

These stablecoins aren’t just popping up out of nowhere. Someone is making money off their creation. I told you at the start of the article that stablecoins are important because we need a medium of exchange, store of value, and unit of accounts — however, this is for the average person. I also said that stablecoins like DAI are a form of debt: someone is taking on the debt to get these good currencies into circulation. This means that the incentive to mint these stablecoins better be really good.

Let’s talk about that.

Creation of Currency (Debt)

Now, the exact date that currency was created is debated, but we can imagine it went something like this.

Person A: Hey, I’ll trade you 10 carrots for 50 tomatoes

Person B: Sounds good, but hey my tomatoes are back at my house. Can I give you these 50 signed rocks as a promise to get you the tomatoes?

Person A: Sure

Boom. 50 signed rocks are now money. 1 signed rock = 1 tomato from Person B.

Person A can now run around and trade these 50 IOU rocks for other stuff around the village. These IOU rocks though represent debt; they are the debt of Person B. At some point, person B needs to fulfill their debt (i.e. give the holder of a signed rock 1 tomato).

In the DeFi and stablecoin world, creating stablecoins works the exact same way. When you mint DAI, RAI, or most other stablecoins, they represent debt that you need to pay back to the system at some point, otherwise risk constantly paying interest.

Oddly enough, you could make the same argument that US dollars are debt, but the argument gets a lot more complicated. Some might even argue that all money is debt.

Creation of Stablecoins

So, if in order for me to create a stablecoin, I need to take on this debt, why would I want to do this? Not only that, but most of the minting of these stablecoins or swapping the stablecoins for their collateral has some sort of fee associated with it! If we look at one of the most popular DAI minting vaults, we see a fee over 2%! If we look at RAI, we see it’s over 0.1%! Even USDC and USDT need to pay fees to swap your dollars and their tokens.

This means that whoever creates DAI, RAI, etc is paying a little extra. If I want \$100 in DAI, I need to put down over \$100 in collateral and pay maybe \$2 in fees! Why would anyone do this? The normal users can’t be doing this, since spending $2 to get some silly stablecoin doesn’t seem worth it. So who is minting these coins?

Well, this leads me to what I think is the most important part of this whole article.

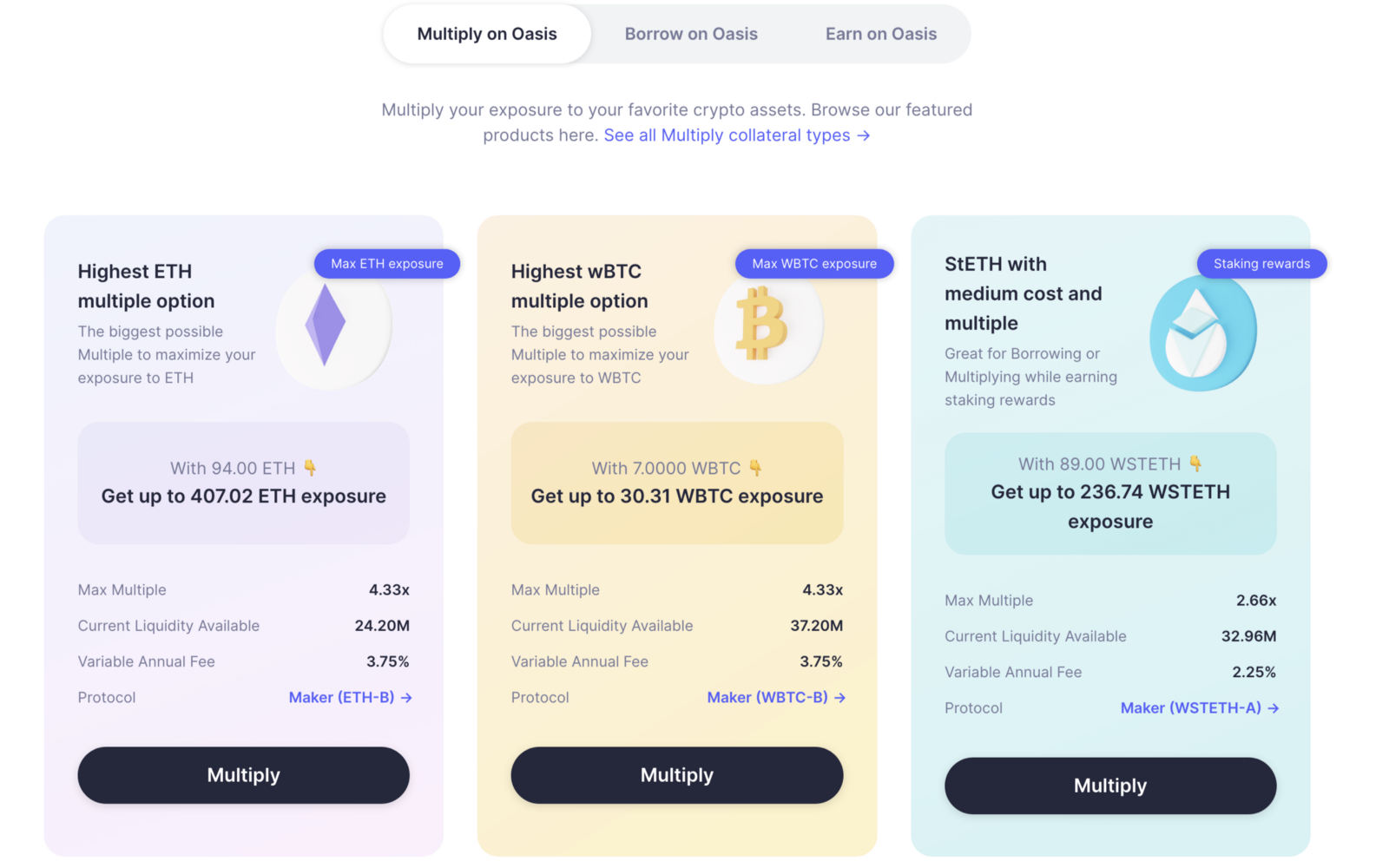

Stablecoins are not minted because we need a good medium of exchange, unit of account, and storage of value. They cost money to mint. Stablecoins are instead created for sophisticated investors to take leveraged bets or earn subsidized yields.

It’s funny.

Why are stablecoins good? -> Because we need currency!

Why are stablecoins minted? -> Because investors want to make leveraged bets.

If I am an investor, and I think ETH is going to skyrocket in price, what can I do? I can put my ETH down as collateral, take out a loan of a stablecoin, and then use that stablecoin to buy more ETH!

In fact, multiplying your exposure to ETH or BTC exposure is the first thing the most popular DAI minting protocol shows you how to do!

Now this is where investors have to do their due diligence. With so many choices, they need to understand the fees associated with every stablecoin so they can pick the coin they think they will have to pay back the least when they are making their, to quote Cardi B, “Money Moves”.

In a weird way, some stablecoin system designs can misincentivize creators to mint a stablecoin with a greater likelihood to fail, since if the coin fails, they won’t have to pay anything back (in terms of value, since if the coin crashes and is worth $0, they will be able to get a lot of coins cheaply). Users of the stablecoin are incentivized to hold onto the stablecoin with the best chance of staying alive so that they don’t lose their life savings if that’s where they choose to hold it.

And all these fees that I’m talking about? These fees go to the stablecoin protocol treasuries. This is why we see so many stablecoins pop up.

What’s the Deal With the Curve Wars?

Now here’s the next thing, you might have heard of the Curve Wars before. Curve.fi is one of the behemoths of DeFi. It’s an AMM (Automated Market Maker) decentralized exchange with a gas-efficient algorithm for swapping stablecoins.

This means that if you want people to buy and use your stablecoins, you better get them onto Curve. This way people can move in and out of debt positions across different stablecoin protocols much more effectively, and that is why Curve is the monster that it is.

Curve facilitates these stablecoin protocols to be substantially more composable.

And everyone wants a piece of the action.

Final Thoughts

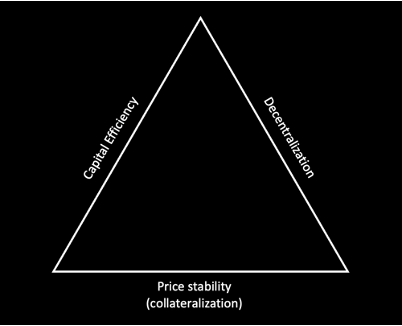

A lot of people look at stablecoins and think there is a trilemma at play.

A stablecoin can be two of the three. I’m not so sure I agree with this trilemma, but we are still working it out.

Stablecoins are an incredibly important piece of making sure Web3 works. We need a token that people can transact in without the spikes and volatility of native blockchain assets.

There is a lot of work to be done. I’ve started by creating a DeFi-minimal repo with some stablecoin architectures that you can take a look at and hopefully learn from. As of now, we have a pegged, governed, exogenous coin and a pegged, algorithmic, exogenous coin for minimal examples.

Hopefully, we can get some more examples in there, and devs can build something even better.

Thanks all, hope you learned a lot here.

The opinions expressed within this post are solely the author’s and do not reflect the opinions and beliefs of the Chainlink Foundation or Chainlink Labs.